The US Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) added 11 Chinese companies to BIS’ Entity List on July 22, 2020, as part of the continued US response to China and in connection with China’s alleged human rights abuses against Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other members of Muslim minority groups in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). These 11 companies are not the only entities that have been added to the Entity List in recent weeks. For example, 24 more Chinese organizations were added to the Entity List on June 5, 2020 for similar reasons.

In this blog post, we explain what these recent export controls on China mean, where sanctions still fit in, and how it relates to the broader US-China conflict.

What are these export controls, and how are they different than sanctions?

Companies on the Entity List are targeted by export control restrictions. These export control restrictions generally mean that US-origin goods, materials, software, and technology (collectively, items) – including non-US items with a greater than de minimis amount of US content – require a BIS license to export, re-export, or transfer to Entity Listed persons. Export controls are different than sanctions: export controls do not impose a blanket prohibition on US-related dealings with listed persons, however, US export controls follow US-origin items and components around the world whether or not a US person or US territory is involved.

In recent months, the US government has increasingly used export controls, and Entity List restrictions in particular, in the same way as (or perhaps as an alternative to) sanctions. Sanctions have traditionally been the primary trade tool used to apply pressure to foreign regimes in order to achieve political goals, whereas export controls have typically been less political and more focused on technical or national security concerns. It has not been uncommon, however, for export control restrictions to follow the imposition of sanctions.

US export controls on China and Chinese companies have been on the rise for several years, notably since BIS imposed a Denial Order on ZTE in 2018. The most significant recent export control actions against China occurred when BIS added Huawei to its Entity List in 2019, continued to ramp up restrictions on Huawei, and (effective June 29, 2020) terminated certain export control licensing exceptions and expanded military end use restrictions for China.

Are sanctions still a concern for these and other Chinese companies?

It is possible that sanctions may follow these export control restrictions because a number of sanctions programs target companies for essentially the same conduct that led to these Entity Listings – e.g., allegedly contributing to human rights abuses in the XUAR. Chinese companies on the Entity List that are less well-known internationally, smaller, or less critical to global supply chains could be at a greater risk of becoming sanctioned.

We are already seeing other, non-China-specific sanctions programs in use against Chinese companies for similar alleged activities. The most decisive sanctions action against China in this area to date come from the US Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), which on July 9, 2020, added four Chinese officials and one Chinese government entity to the List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN list) in connection with alleged human rights abuses against ethnic minorities in the XUAR under the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act. On July 31, 2020, OFAC added another two Chinese officials and one other Chinese government entity to the SDN list “in connection with serious rights abuses against ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR)”, again under the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act.

Additional sanctions may also be forthcoming under the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act (UHRPA), signed into law on June 17, 2020, which requires, “The President [to] periodically report to Congress a list identifying foreign individuals and entities responsible for such human rights abuses.” In an unusual step, several US government agencies issued a joint Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory on July 1, 2020 that warns companies of, “potential exposure in their supply chain to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang) or to facilities outside Xinjiang that use labor or goods from Xinjiang should be aware of the reputational, economic, and legal risks of involvement with entities that engage in human rights abuses, including but not limited to forced labor in the manufacture of goods intended for domestic and international distribution”. Although the advisory and UHRPA do not impose sanctions, they caution companies of the potential perils of engaging in certain activities and may be harbingers of future sanctions or other actions.

How does this fit into the wider US response to China?

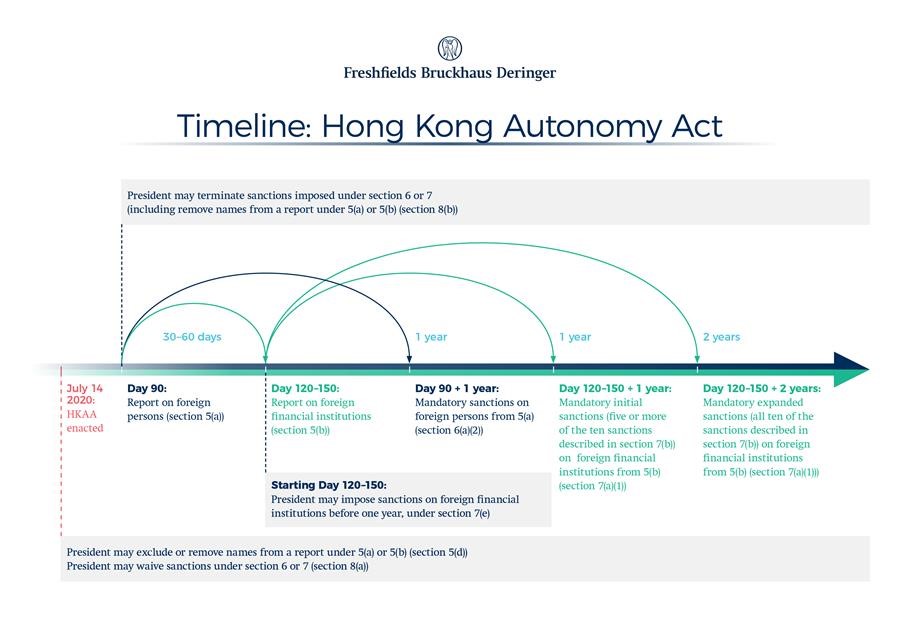

These export controls coincide with a number of other recent actions, including the HKAA and the termination of Hong Kong’s special status in July 2020. Please see below our timeline of recent US action against China, as well as our lengthier client briefing on the full range of recent US responses.

As covered in our briefing, the US response to China, which has garnered broad support across the political spectrum, has thus far included:

- the expansion of Chinese telecom and technology export restrictions, as well as the targeting of additional companies (Export Administration Regulations; DOD List; FCC);

- sanctions designations and warnings related to Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Tibet (Global Magnitsky; UHRPA; Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act of 2018);

- a new sanctions program targeting foreign financial institutions (HKAA);

- Hong Kong increasingly being treated the same as mainland China through the removal of the so-called “special status” (United States-Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992; Executive Order on Hong Kong Normalization);

- a Hong Kong arms embargo (International Traffic in Arms Regulations);

- the termination of Hong Kong export control preferences (Export Administration Regulations);

- threatened delisting of Chinese companies (Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act);

- the introduction of COVID-19 and Hong Kong retaliation bills (COVID-19 Accountability Act); and

- potential US dollar restrictions.

Conclusion

As the US-China trade war and conflict continues, further US action against China should be expected, including the increasing use of export controls and sanctions as foreign policy tools.